Everything comes from somewhere, from someone, from the subconscious or the conscious. The saying “good artists borrow, great artists steal” is ubiquitous, and the way in which artists are influenced by each other is foundational to image making. The entire practice of graphic design is built upon the usage of letterforms that are often not drawn by the designers who use them. Conversely, artists accusing another artist of ripping off their work is equally ubiquitous. As an image maker, I can say from experience that feeling like your work has been copied or stolen without attribution can be truly maddening. In the small world of graphic T-shirts, recent fights include Cara Delevigne burglarizing an indie brand, Reformation stealing from Jimmy Kimmel’s daughter, and Dolce & Gabbana ironically ripping off call-out Instagram Diet Prada. But who can you call if your image has been stolen? What happens when an artist gets arrested? Would you steal a painting? What about a color scheme? A piece of clip art? A composition!?!

In the United States, the legal construct of originality has come to rest on what’s called “fair use”. By definition, fair use is “a legal doctrine that promotes freedom of expression by permitting the unlicensed use of copyright-protected works in certain circumstances.” Anyone can use any piece of copyrighted material under the doctrine of fair use. In basic terms, you can use copyrighted material without a commercial license if you remix the work enough, do it for non-commercial means, or use it in a setting where the marketplace does not confuse the work for something else. More specifically, something is considered “fair use” as long as the usage falls within these four qualifying factors, as outlined in Section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976:

the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

This point deals with how the party claiming fair use is using the work, and typically nonprofit educational and noncommercial uses are considered fair. It also concerns itself with this idea of “transformative” use cases. In this definition, “‘Transformative’ uses are those that add something new, with a further purpose or different character, and do not substitute for the original use of the work.” A nearly impossible thing to quantify in terms of visual art. Would a shift in color considered “something new” or could a crop on an image create a “different character”? When it comes to art, transformation and purpose and character are fluid and ill-defined.

the nature of the copyrighted work;

Courts look at this factor in terms of the source of the work, whether it be informational or published. If the source referenced is a fact it is more fair use than fiction, and taking inspiration from a non-artistic place is considered the more legal route.

the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole;

With this factor, “courts look at both the quantity and quality of the copyrighted material that was used”. If you use a smaller piece its considered fairer than a larger one, which is easier when it comes to writing, but can be much harder to quantify when it comes to art. If you’re hacking off the corner of a painting, that can be shown, but what of form, color, composition, ethos? Art is not something that typically works in percentages and this is not an easily definable factor when it comes to visual form.

the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The fourth piece in assessing fair use is the impact of the use on the prospective market of the copied work. When the purportedly infringing work negatively affects the original work's market, this weighs against fair use. The market has little to do with the creation of art, but if one were to make something that would intentionally infringe and supercede and original work, this would apply.

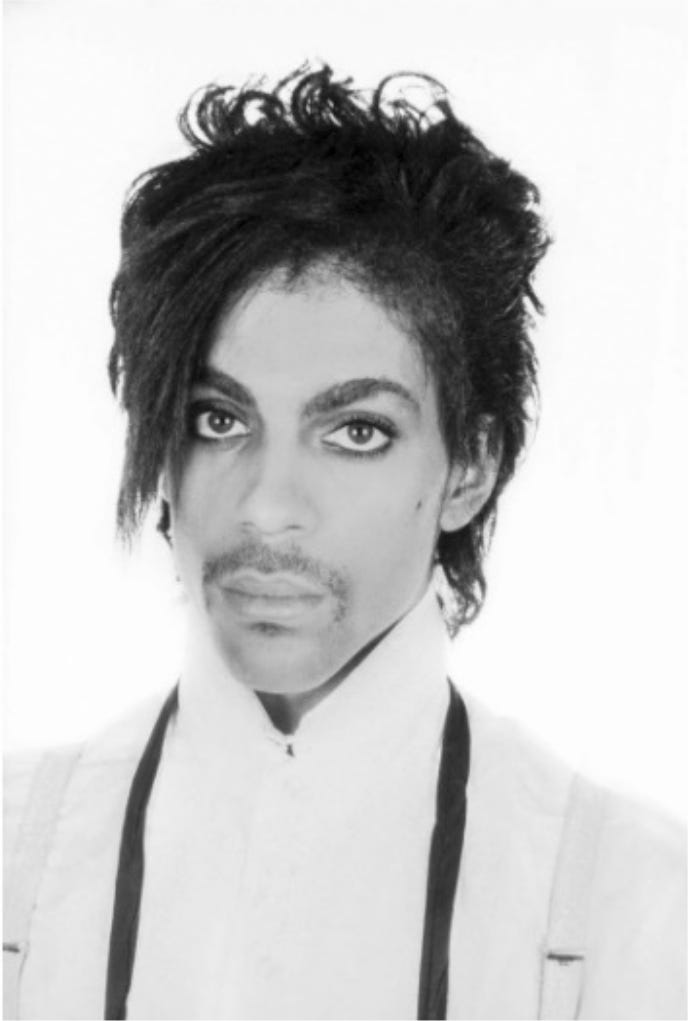

Most recently, legal debates over “fair use” has taken center stage and become a war of conflicting interests, manipulated by the machinations of power familiar under capitalism. In May 2023, the U.S. Supreme Court, with a majority vote of 7-2, ruled that Andy Warhol infringed on photographer Lynn Goldsmith's copyright when he created a series of silk screen images based on a photograph Goldsmith shot of the late musician Prince for Newsweek in 1981. The question at hand was whether Warhol's Prince images sufficiently transformed Goldsmith's photograph, exempting them from claims of copyright infringement under the doctrine of "fair use."

At the time, the magazine commissioned Warhol to create a silkscreen work based on Goldsmith's photo, which they featured in an article about the musician. They then licensed the photo from for a one-time use and paid her $400 (a rate that hasn’t changed much for those of us who work in media in the forty years since). In 2016, after Prince's death, Condé Nast used the same image for the cover of their special edition magazine issue "The Genius of Prince." They paid over $10,000 to the Andy Warhol Foundation (AWF), which holds Warhol's copyrights, for a license to use a different print from the series called "Orange Prince." The image was then published without giving credit or payment to Goldsmith, who recognized her own work and claimed copyright infringement. When she showed AWF the agreement in 2016 for one-time usage and credit in 1984, after some discussion they sued her in an accusation of extortion. They later offered $15,000 and promised to fight the case all the way up to the Supreme Court, and Goldsmith called their bluff.

Eventually, the Supreme Court sided with Goldsmith, and in their opinion, as stated by Justice Sonia Sotomayor: “Goldsmith's original works, like those of other photographers, are entitled to copyright protection, even against famous artists. Such protection includes the right to prepare derivative works that transform the original. (…) In this case, however, Goldsmith's original photograph of Prince, and AWF's copying use of that photograph in an image licensed to a special edition magazine devoted to Prince, share substantially the same purpose, and the use is of a commercial nature.” Now this is all well and true, in that the purpose of the two images is essentially the same under the first factor of fair use — two magazine covers decades apart — but did Goldsmith actually have a case at all if Warhol had originally transformed the piece back in 1981?

In Justice Elena Kagan's dissenting opinion, she stated: "It will stifle creativity of every sort. It will impede new art and music and literature. It will thwart the expression of new ideas and the attainment of new knowledge. It will make our world poorer." and I have to agree. I would argue that the work that Warhol did was transformative both in form and purpose — it was re-cropped, one layer was silhouetted, it was saturated with color, drawings were added and it expanded into a series of paintings. Warhol is far from the most “original” artist, but what he did was all good and well under fair use. But ultimately, the idiom that “all art is subjective” rings true, and I think it’s impossible to truly quantify the level of “transformation”. Unfortunately the social structures in place isolated Goldsmith and she found herself powerless under the weight of AWF and the cutthroat NYC media world. Ethically, I would argue that she had no case, but morally, I’m on her side.

As an image maker, at best, our work can help define visual culture through our expression, and ideally allow that expression to be disseminated and transformed through imagery. When I see this stylistic influence duplicated, I consider it a mark of success — especially if it is a fellow artist or student. However, predatory corporations or artists in power often leech from individual expression, profiting from cutting corners and choosing not to hire the originators of specific pieces, plucking designs from Pinterest, collaging styles from a moodboard, creating derivative works and hurting artistic communities by creating a lack of resources to the artists. A version of this scenario happened to Goldsmith when AWF breached her agreement in 2016, and it’s not surprising that she chose to take on those who were exploiting her. When artists are ripped off, they can feel powerless, and calling out a corporation can seem like the only way to reclaim power instead of finding solidarity with those who stole from them — yet may have been unable to pay. Capitalism often chooses dictates that praise be given to the individual, promoting a vision of creativity that isolates and commodifies the artist. Being “original” is a lonely place to be, yet this stylistic originality rarely emerges from the isolated individual, but from the interplay of ideas and influences within or without a community.

The broken structure of the unelected Supreme Court and the damage it has wreaked on American society — as recent decisions on abortion, affirmative action, and debt relief have shown — should not decide what is fair and good in aesthetics. If you want to understand the negative impact of fair use on the art world, look no further than the impact that it has already had on the music world. De La Soul was sued in 1991 for their seminal work Three Feet High and Rising only to have to rework their samples decades later after additional fights with their label just to get their work on Spotify. The Marvin Gaye Estate won a case against Pharrell and Robin Thicke’s problematic jingle “Blurred Lines” just based on musical influence alone. I fear that the same could happen to visual artists, blocking them at every corner for using pieces under a distorted lens of law. It’s stifling to see how the law, capitalism, and society have all pitted us against each other.

For decades, the concept of “fair use” has provided protection for artists, allowing us to remix and reuse without fear of legal retribution, but it has become antiquated, and broken, and needs to change to accommodate visual artists. In truth, the structure of the Supreme Court is archaic — and current justices are knowingly and deeply corrupt — and really the whole system should be abolished and reborn. Under our current power structure, I would argue that the law should somehow be redrawn to accommodate aesthetics, or not get anywhere near the visual arts. If a law about art should exist, it should say that no one truly owns visual culture, and anything is allowed when it comes to aesthetics. While I appreciate fair use and its protections, but it is far from perfect, and under capitalism corporations often exploit the law for their own gain instead of protecting artists. Those in positions of power — the true beneficiaries of fair use — should be paying artists. Artists should not be afraid to take from others in order to advance aesthetics forward. After all, it’s only fair.